What

is known as the ‘creative’ process is a mysterious act that

engages theorists and analysts, academics who specialise in rational

thought and review outside of the artists’ world. It is as if they

might know. Yet the attempt to establish some sense and understanding

of the process is still made. One wonders why, because it has

frequently been pointed out that the process is not a matter of

applying any rules or patterns of thought to a situation, no matter

how inventive these might appear. The artists’ act is more than reasoned invention.*

Occasionally

artists write about their experiences and try to offer insights into

their different world. Their efforts to explain their emotional

journey, their ‘creative’ enterprise, seek to elucidate events

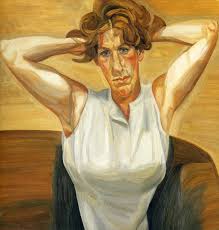

for others to comprehend. Only once in his life did Lucian Freud

write about his experience of painting. Towards the end of Freud’s

life, Geordie Greig tried to get him to once more write about his

art. Freud was reluctant, and, after some thought and time, simply

confirmed his previous text and added a few cryptic notes to it.

Greig published these comments along with the original writing in the

Tatler.

Geordie Greig

The following are a few notes on the subject recorded from Breakfast with Lucian A Portrait of the Artist by

Geordie Greig. It is interesting to read the words in association with some of Freud's paintings.

Lucian

Freud, in spite of his unique lifestyle, liked his privacy. He hated

to be watched. He disliked blatant promotion, but did enjoy its

outcomes in spite of this position. He wrote about his act of

painting only once, in Encounter, [‘Some Thoughts on Painting’], a publication edited by

Stephen Spender.

Freud's mother

Lucian

had not seen a copy of Encounter

for decades and enjoyed seeing reproductions of his pictures . . .

As we sat in Clarke's (the breakfast venue) I read aloud

part of his 1954

essay . . . 'My object in painting pictures is to try and move the

senses by giving an intensification of reality. Whether this can be

achieved depends on how intensely the painter understands and feels

for the person or object of his choice.'

Francis Bacon

His

views had barely altered . . . The original words, Lucian said, had

been hard-wrought, chosen with the same perfectionist zeal with which

he applied paint, almost chiselled from his mind. He had expressed

disdain for abstract art, arguing vigorously the case for the

superiority of figurative art: 'Painters who deny themselves the

representation of life and limit their language to purely abstract

forms are depriving themselves of the possibility of provoking more

then an aesthetic emotion.'

Freud's mother

He

believed the human body was the most profound subject and he pursued

a ruthlessness of observation, using the forensic exactitude of a

scientist dissecting an animal in a laboratory. . . .

I

carried on reading: 'The subject must be kept under closest

observation: if this is done, day and night, the subject – he, she,

or it – will eventually reveal the all without which selection

itself is not possible; they will reveal it, through some and every

facet of their lives or lack of life, through movements and

attitudes, through every variation from one moment to another.'

Queen Elizabeth 11

The

essay was a justification of his way of life. 'A painter must think

of everything he sees as being there entirely for his own use and

pleasure. The artist who tries to serve nature is only an executive

artist.’

. . .

His

ambition, he had written in Encounter, was to give ‘art complete

independence from life, an independence that is necessary because the

picture in order to move us must never remind us of life, but must

acquire a life of its own, precisely in order to reflect life.’

David Hockney

. . .

His

new, very short manifesto contained his final published words. ‘On

re-reading it [‘Some Thoughts on Painting’] I find that I left

out the vital ingredient without which painting can’t exist: PAINT.

Paint in relation to a painter’s nature. One thing more important

than the person in the picture is the picture.’

Francis Bacon

Freud started painting from one point, finishing the parts as the picture developed

. .

.

On

the walls of his studio were scribbled three words: ‘urgent’,

‘subtle’ and ‘concise’. He explained how those words defined

his purposes: (see p. 130 - 131)

Breakfast

with Lucian Vintage Books, London, 2015: p.128 – 129

♥

'the greatest British painter of the past one hundred years.' TOM WOLFE

‘He

said that the important thing in painting is concentration; he

stressed this as if it were a revelation.’ (p.161 BWL) #

Lucian

aimed for a higher truth through intense observation . . . ‘Lucian

saw the world more differently than most. There was an acuity and a

penetration in his scrutiny of your face and in his search for the

smallest details of appearance as a clue to character.’ (Sir

Nicholas Serota, director of the Tate) . . . ‘I hope that if I

concentrated enough, the intensity of scrutiny alone would force life

into the pictures,’ (Lucian Freud) (p.163 BWL)

♥

*

Goodhart's law is an

adage named after economist Charles Goodhart, which states: "When

a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure."

This follows from individuals trying to anticipate the effect of a

policy, then taking actions which alter its outcome. In art, the 'law' becomes: once something useful has been measured and applied, it ceases to become useful.

The description of the traditional craftsman's method is: Having concentrated, he set to work.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.