For

many years now,

researchers have been thinking

about brochs, wondering how these

structures were erected. A process has been proposed, see -

https://voussoirs.blogspot.com/2017/01/on-brochs-enigma-of-meaning-form.html

This technique used the geometry of constructing a circle without

knowing its centre. Here, with this method, the focii of an ellipse

formed by two posts of the six that have been assumed to be at the

centre of the broch, are used to draw the close-to-circular curve at various

locations. It is not an exact strategy, but is one way to approximate

a circle without knowing its centre or being able to easily access

it.

A far more accurate

system based on the use of simple pegs and string, seems to be

possible as an alternative to this rough method. It adopts a similar

strategy, almost being a variation of it; but it is a far more

accurate and elegant method. It is discussed in this site: see -

https://math.stackexchange.com/questions/862915/how-to-create-circles-and-or-sections-of-a-circle-when-the-centre-is-inaccessibl/862940

The chat starts with the question: how does one draw a circular arc

without knowing or having access to the centre, for

landscaping paths, garden edges, etc.? One idea uses the

principle that says that the angle suspended by a chord of a circle

is always the same for the same chord. So string and pegs can

precisely manage a circular arc without knowing or using the centre;

but what of a whole circle? How does one arrange the continuity of the arc, its coherence in

circular rigour?

We

know the length of the chord, so a piece of string kept at the same angle can easily

define an

identical arc

from this same line

length, giving the same portion of circle anywhere;

but the orientation of this chord length

is critical if one is to define a complete circle.

The position of the new chord, (of equal

length), must be aligned such that it is a chord of

the same circle as that which the

other chords relate to.

The best, perhaps the simplest beginning for the definition of

this circle is to use an equilateral triangle, or

indeed, any

geometrical shape that can be simply delineated and will

fit within a circle. An arc

can be structured off each of these chords, (three in the case

of an equilateral triangle), which, being the same and related to the

same circle, will describe a circle when the suspended angle is

always 120 degrees. Various other alternatives of inscribed shapes

are possible, all of which will have different suspended angles –

e.g. 135 degrees for a square; 150 degrees for a hexagon. Without the

exact angle appropriate to the shape, one will get, e.g. for an

equilateral triangle, a trefoil form or a similar deformity; a

quatrafoil form for a square; etc.

Typical broch plans

To set out a circle,

one could start with a compact form, say a hexagon, (a circle with the

radius marked out along the circumference as six equal chords),

extend the alternate sides into an equilateral triangle, and use the

sides of the triangle as the chords from which to suspended an angle

of 120 degrees. One could ask: was the hexagon the start of the set out of the broch? The inner

arrangement of

posts could be

easily defined

and expanded to give the locations of the

larger triangle

for the larger circles by marking off

points on the lines extended from the centroid of the triangle

through each corner of the form. It

may seem strange that one starts with the centre of the circle, (for

the hexagon), and then does not use it for

the setout. The complication comes with height. While it is simple

enough to use pegs and a string to draw circles

on the ground, and work up from these

markings, matters become complex when

things might get in the way, such as

scaffolding. It is difficult to extend the

centre line vertically as a line to a

higher point in space without some fixed

references. It is much easier to extend a

structure up, say a braced set

of six posts, to define the 3D location,

but this complicates the access to the

centre. So the idea of the circle being able to be drawn without

access to its centre has to be contemplated. It

is neither impossible, nor difficult.

The

set out of the circle can

be managed with pegs, a string, and a template with three pegs

positioned at an

angle of 120 degrees, (if one is starting

with an equilateral triangle). By fixing

the string at one peg, (one

corner of the triangle),

and having a second person pulling the

string around another

peg on a different corner of the triangle

such that the string forms an angle of 120

degrees on the guiding

template, the

point of the

template will be able to define a point on the circle.

The template could be repeatedly manipulated into various

positions

such that the string touches all three pegs at

120 degrees as well as the second chord peg,

with the apex peg on the template defining the various

locations

of the points on

the circle in which the equilateral

triangle sits. This

process can be repeated

for each side of the equilateral triangle to

give one the complete

circle. This

accurate set out can be achieved with two people, pegs, a length of

string, and a template with pegs set out to define the angle of 120

degrees, an angle

that is easily

set out by drawing a hexagon. This is a process requiring only

one peg and one string. The angles between

the sides of a hexagon are 120 degrees.

It is interesting to

observe the plans of round houses and wheel houses. These

illustrations show posts located in relation to the surrounding

circular wall in the position required for this peg-string-template

set out process. One can check this by extending the sides of the

hexagon to make an equilateral triangle that touches the surrounding

wall.

The set out from the hexagonal post arrangements using pegs, string and template

Typical round house

A set of twelve posts can give a hexagon, square, or an equilateral triangle to set out from.

What we do know is

that dry stone builders do not do anything freehand – they

use strings and profiles. Strings can draw arcs and manage

profiles, even ellipses and circles,

accurately, as has been described, so

it all seems to be a

reasonable beginning.

The other controls required

for construction relate to horizontals and verticals - to

levels, and the vertical continuity of the whole. The

solution to these issues are simpler than

the drawing of the circle, but similarly

require string, a timber template, and

an additional weight.

The plumb bob can

be used to define the vertical projection,

as well as the horizontal alignment. Shetland

has an old, but simple and effective

level. It is a

forty-five degree triangular template

made up as a timber frame, with

a plumb bob hanging from the ninety degree

intersection. The

centre line of the hypotenuse is marked

off as a base scale.

The alignment of the

plumb bob string

with the centre line mark positions the

hypotenuse on the true horizontal. It is an

ingenious device

that would have been easy for broch builders to both

make and manage at

all sizes for various types of tasks.

Any isosceles triangle will do too, but the

45/90 set out is simple, and provides the mason with a square and the

45 degree angles. With

any other triangle, the centre line of the base of the triangle will

be the marker for the string suspended from the apex. The

hypotenuse/base element can extend well beyond the scope of the

triangle so as to provide a good length for the gauging of the

horizontal level along or between elements.

As

for broch

verticality and

continuity – a centre reference solves

this. Even the modern laser scans

of the broch use a vertical centre line as a primary

reference. We

could hypothesise that

the six posts were

the start of the set out, each

being set up vertically, and became

the vertical

reference points

that carried the

walls up in their

desired alignments. When

dry stone walls are built today, profiles are used to control the

planes. One can assume that broch builders used a similar technique.

So while we can devise techniques to

describe processes that could have been used in the set

out of the broch, the

question is: what holds the profiles

for the

upper levels? Might it be the

scarcement? Was it the

scaffold? Was the inner structure both the

scaffold and the permanent fit-out?

A laser scan of the interior of Mousa broch.

Temporary scaffolding may have also been used internally along with the permanent framing.

Externally

we can propose a system of scaffolding that leaned against the

finished walls, being propped up and out from these as they

progressed, providing a working platform that did not require

scarcements.

Projections could have been avoided

externally so as to improve security; to not provide anyone with a

ledge to use for climbing. In all of this

speculation, one has to come to terms with the other question: how

were the masses of stone managed? Even with a small dry stone

structure, one is amazed at the quantity of stone that becomes

the pile of

rubble once the old walls

have tumbled down. The quantity

of stone needed for the broch would have been enormous.

How was the stone lifted for the

work to continue up to thirteen metres, (Mousa)? The

mason must have had

a plentiful supply of stone close by because the

process of building the dry stone walls involves selecting and picking up what

seems to be an appropriate stone and

finding a place for it; and doing this time and time again. It

is a different process to laying dressed stone. It

would not make sense for stones to be transported from the ground one

by one as the dry stone mason

required. Reconstructions have taken brochs

up to working heights manageable from

the ground level. The challenge is to discover how the rubble was

handled at the upper heights. One could perhaps guess that stones

were stacked on the inner and outer scaffolds, and continually

replenished to maintain the stockpile. This

means that the scaffolds must have been fairly substantial

structures, both in size and strength.

What

we do know is

that gravity has not changed, and neither

have the juxtapositional forces of stone on

stone, or of timber on stone. We should be able to re-imagine the

process once we have some degree of certainty about the

available processes

that we can suppose

involved the use of templates, profiles, string, pegs, and weights,

because we still use these today, almost in spite of our clever

technology: isn’t a laser merely a flash piece of string?

On the scarcement:

this ledge looks like a change in construction strategy. It is such a

self-conscious element that it must have a significant purpose. Was

it there to hold the scaffold; maybe the upper profiles? Was it there

to support the floor as well? How were the wall profiles managed? -

see:

https://voussoirs.blogspot.com/2017/01/on-brochs-enigma-of-meaning-form.html Was the scarcement there to do all of these tasks? Multi-function

appears to hold some logic in the interpretation of these times of efficient frugality with

materials and energy. It is this latter feeling, an assumption, that

gives one the idea that brochs had a definitive purpose beyond

display and intimidation (Smith), qualities that maybe still played an

inclusive, integral part of the dominance in appearance.#

It is not clear if the galleries actually have any floor space.

The void is bridged by separate stone ties.

Some researchers

seem to support the idea that brochs were constructed from the void

between the walls, without scaffolding. It is certainly an intriguing

idea, but it has its complications: see -

https://voussoirs.blogspot.com/2017/01/on-brochs-enigma-of-meaning-form.html It is not too difficult to envisage the erection of the broch up to

the scarcement height. Things to this level appear to be readily

manageable from the ground, with traditional setout techniques and

small scale scaffolding. It is above this level where things get

tricky. The walls become twin dry stone walls that continue up to

greater heights, to 13 metres in the case of Mousa. So how were these

walls erected?

The 3D scan suggests a lower scarcement too - see *

One could just

suggest that there were scaffolds that were erected for the work.

Scaffolding can easily be pieced together for almost all

circumstances: but might iron age man have been so generous with his

materials and effort? It has previously been argued that it is not

reasonable to suggest that the broch was built overhand from the

space between the walls. One could simply suggest that planks were

used to span the bridging stones to provide the work support, but the

finish of the exposed surfaces of these walls seems too perfect to

have been erected from the ‘away’ side. Supposing that the base

of the broch was erected and completed up to scarcement height, then

his mass would have provided a working surface for the masons to

erect the walls spirally, working on the ends of the walls, and

moving backwards in a spiral as the walls progressed, moving up to

the next level once one circumference has been completed. At least

there would be some continuity in work location.

The scarcement has frequently suggested a floor level.^^

Smith argues for it being there only for scaffolding.

This might seem

reasonable, but there are issues to be answered: can a dry stone wall

be built from the end and give the finish we see at Mousa? Even if

this might be so, one has to answer the question: how were the

massive quantities of stone supplied to the masons. Here one has to

speculate that there were intermediate scaffolding platforms erected

both inside and out for the piles of stone to be placed on. The

question this raises is that, given that this scaffold for the stones

exists, why would it not be used as a working platform for the masons

to build the walls directly in front of them, maybe one team outside

and one team inside?

It seems that the

full sensing of the progression of the work is essential for the

mason to contemplate, consider, and assess, as he picks up each stone

and, as the rule seems to go, places it. A stone is never put

back to be rejected for another; it is always used. The skills

involved in this technique require a precise and comprehensive

understanding of both the pile of stones and the walls in relation to

the mason’s body and hands that makes demands that are not

negotiable. The stance of the mason and his mental state, along with

his coherence and well-being, is critical to a good outcome – both

efficiently, visually and structurally. One is inclined to confirm

the extensive use of scaffolding that, as with the idea of the spiral

progress, could, perhaps, have been segmental and was moved around

progressively to suit the programme. Internally, it seems that the

idea of the vertical growth of the scaffold that could also be used

for alignments and set outs, and left as permanent structure, seems

the better option to promote.

There are always

many competing issues for one’s consideration in these matters, but

the peg, string, template and plumb bob concept along with the idea

of permanent internal scaffolding and temporary external scaffolding,

seems to hold more coherent logic than most suggestions. This inner

and outer scaffold would be able to provide good support for the

manipulation and set up of the walling profiles, and for the piles of

stones that are required near the masons. Once the dry stone walls

have been completed, parts of the external scaffolding could be used

as the roof framing, with the upper perimeter walkway being the

working platform for the roofers – for the framing and the

thatching, whatever this arrangement might have been. The intramural

stair is able to provide easy, permanent access to this upper level,

but is unlikely to have been a main access point during construction. Lifting devices

must have been used – simple ropes, baskets, pulleys and levers.

This model draws scarcements that do not exist.^^

There is little hope of any resolution when researchers invent possibilities.

One could ask why

there is only one internal scarcement that seems to attract the

attention of most researchers, prompting the popular view of there

being a floor at this height. Smith has struggled with this matter

and, along with his ‘no roof’ theory, has preferred to see the

scarcement as a support for scaffolding. One has to realise that the

scarcement is located at the top of the lower wall mass of the broch. Above this

level the walls become thinner, twin elements tied with bridging

stones.^ It is very likely that this ‘lightweight’ structure is

unsuitable to provide the mass and stability required for the

restraint of another scarcement for a higher floor level.+ The height

of the void, (Mousa), has always been a concern for theorists trying

to fit the broch out. Some solutions are just silly.* So it is that

the idea of an inner frame supporting two timber-framed levels

sitting on the scarcement seems to have good structural sense, as

does the continuation of the inner posts to support the roofing

purlins, and provide the continuous, vertical set out reference for

the whole broch. The intramural stair is, of course, an access that

would always have been available to reach the working level of the

broch as the stair was raised with the walls.

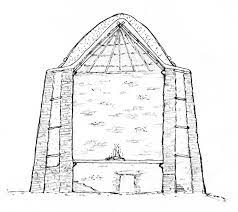

Might the roof have been raised off the central purlin structure in order to provide light and ventilation?

Considering this

overview of possibilities, one could summarise to suggest that the

broch:

was set out from the

hexagonal core;

used fixed internal

scaffolding (and possibly some interim temporary supports too);

used temporary

external scaffolding;

was roofed using

portion of the external scaffolding on completion of the walls;

had two internal

floor levels connected by stairs/ladders;

used only the voids

formed in the base walls below the scarcement;

used the space

between the walls for stairs to connect the lower level with the upper walkway;

did not generally

use the gallery spaces.

The effort to fill the void creates some impossible situations.

One wonders how extra scarcements get to be illustrated (see upper level).^^

Just what the daily

life in these volumes might have entailed is something that becomes

more broadly speculative. The article,

https://voussoirs.blogspot.com/2019/04/the-desert-broch-ksar-de-draa.html,

does start to theorise on this. It seems clear that the broch was a defensive lookout; a place for the storage of food/supplies/special items; maybe a

temporary refuge; perhaps a chapel, a spiritual centre; maybe a

funereal location too. It seems clear that it was a community

structure rather than a private, personal place.

It seems unlikely that the wall openings were used structurally

The inner openings

We can admire the stonework today, but might the habitable areas have been lined?

Might it have been,

like the Ksar de Draa, a store at high levels - the less accessible

places – with the holes in the interior walls providing ventilation

for the control of temperature, humidity and damp so as to overcome

mould?^ The lower level might have been for fodder storage and for

prized animals; the intermediate floor at the scarcement level could

have been a temporary retreat, or a space for worship. It is a structure

that would have isolated the damp base from the comforts of easy

habitation/worship. The principle of the twin wall in construction is

that the external wall can always be damp, with the inner one always kept dry. At

the scarcement, the damp would collect and spread through the solid

base below. One prefers to see the broch as multi-functional: a cosy,

dry, warm retreat from the hub-bub of the village surrounds; a safe

haven for tools, talismans, grains, oils, animals, body and spirit.

NOTES

#

Here one recalls

Ralph Erskine, the English/Swedish architect. At a Brisbane

convention some years ago, he presented his work and explained it

rationally as being functionally formed by briefed requirements and

climate. When asked privately about the self-conscious, ‘sculptural’

appearance of some of his projects, he commented that he never

discussed this ‘art’ aspect of his work as it had become far too

fashionable an excuse for forming, and only encouraged other, maybe

younger architects to forget functional matters. He was saying that

he was aware of both the functional and the artistic shaping in the

one and the same form – both together. One can assume that broch

builders were no different; that it is our limitation that seeks to

place a singular purpose into our theories. In this regard we need to

know much more about the spiritual life of the times too. Older eras

were not like ours; the religious life was integrated into their very

existence, their being. We should be wary of itemised explanations

that rely only on unique, practical, functional interpretations other

than when necessity might demand them, as in rational structural

processes.

*

A close look at the

3D model of the Mousa broch interior suggests that Mousa has two

scarcements, one at about three metres high, the other lower, maybe

half a metre off the current inside ground level. One could easily

propose that Mousa had a lower floor that was at the same level as

the beginning of the intramural stair. Presently, one has to climb up

to this start, an inconvenience that would have been overcome with

the lower floor. That the intramural stair is still accessible today,

suggests it played an important role in the daily goings on in the

broch: see - 3D MODEL OF MOUSA

+

BROCH FAILURES

This is an

interesting article on the Safety of Iron Age

Brochs, their failures:

^

RESEARCH

See NOTES concerning

broch twin wall structure and ventilation in:

https://voussoirs.blogspot.com/2019/04/the-desert-broch-ksar-de-draa.html

^^

On the graphic theories that have been drawn by researchers as cross sections, it is always alarming to see these drawings treated so casually; naively. Frequently structural elements are delineated completely inadequately, with significant structures being drawn as two thin parallel lines. While this approach distorts possible interpretations with fantastical impossibilities, it is far worse to see the existing fabric being invented. If we are unable to clearly determine and document what we have before our eyes, and use this information as a basis for careful, accurate interpretation; and are happy to liberally distort the record by adding bits and pieces to suit out theories, then we will get nowhere very quickly. Rigour and consistency are needed in every aspect of this research so that it can be tested. Personal inventions or simple carelessness does not get past the first assessment.

N.B.

For more on the building of brochs, see:

https://voussoirs.blogspot.com/2019/04/more-on-building-brochs-thinking-doodles.html

NOTE

25 February 2020

see: https://voussoirs.blogspot.com/2020/02/on-planning-meaning-mental-structures.html

^^

On the graphic theories that have been drawn by researchers as cross sections, it is always alarming to see these drawings treated so casually; naively. Frequently structural elements are delineated completely inadequately, with significant structures being drawn as two thin parallel lines. While this approach distorts possible interpretations with fantastical impossibilities, it is far worse to see the existing fabric being invented. If we are unable to clearly determine and document what we have before our eyes, and use this information as a basis for careful, accurate interpretation; and are happy to liberally distort the record by adding bits and pieces to suit out theories, then we will get nowhere very quickly. Rigour and consistency are needed in every aspect of this research so that it can be tested. Personal inventions or simple carelessness does not get past the first assessment.

N.B.

For more on the building of brochs, see:

https://voussoirs.blogspot.com/2019/04/more-on-building-brochs-thinking-doodles.html

NOTE

25 February 2020

see: https://voussoirs.blogspot.com/2020/02/on-planning-meaning-mental-structures.html

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.