What is it that makes a home? The loft space had been fitted out as a study, quaintly accessed with a ladder that cleverly folds away to make a secret place out of this void. This roof space has all been nicely lined and insulated; it feels very comfortable, doubling as a place for the hot water system, with cunning storage spaces at the eaves too; but still it is more study than store or service area.

The room has a comfortable height with a combed ceiling dipping down from a central flat 2100mm panel height about one metre wide, to about 900mm off the floor each side at the walls; just a nice height for book shelves. Some of my books have been brought up here and now line the room. A folding table has been set up in front of a square window in the gable wall as a desk - the work place. This text is being typed on this desk, cleverly through a Bluetooth keyboard onto a tablet. The window has an elevated view of the landscape to the west, with a glimpse of the nearby loch. The real estate blurb would boast of ‘water views.’ The hills are just greening up after a bleak winter, when the browns coloured the slopes that have two small, white cottages sitting on them, looking towards the sunrise. The place is named Houlland; it is on the west of the Loch of Cliff on Unst in Shetland. This vista is framed from Gue. Every millimetre of Shetland has been named: every slope; every nook; every cranny; every inlet; every voe; every knoll: this is ancient land; known place.

We had constructed the addition to the small cottage that was originally built in about 1852. The new build reconstructed an annex that was added in 1946, to provide granny with a toilet, a laundry, a bathroom, and some additional storage space for the original two up, two down compactness of the original dwelling that astonishingly had raised four sons into manhood without these additional conveniences. The new work offered the same facilities as were previously provided by the extension, on the same foundation walls, with new amenities that included a shower in lieu of the bath, and new, efficient machines for the laundry that no longer requires the traditional tubs. Given these efficiencies in size and performance, there was space left over for storage and a sitting area. The concept was to try to make a conservatory room that was not a conservatory – a space that was well-glazed and could feel open to the landscape that stretched as a vista to about five miles south and one mile west: these distances felt good to the eye; comfortingly familiar, yet constantly surprising. They revealed the ever-changing light and colours of the seasons and the crofting cycle.

The existing flat roof that seemed to be an essential variation to the theme after the destructive winter gales of 1992, was replaced with the original gabled form matching the pitch of the slate roof of the old cottage, thus providing the loft space that is the study. It was the return to this study after some months of absence that prompted the emotions that raised these thoughts. There was nothing grandly dramatic, just a feeling of being home, that stimulated the thoughts about home, and home-coming. The space had barely been used prior to this. It had been a convenient space for storing the building junk out of the way, but now the room had been painted, nicely finished off, and fitted out with the desk and the bookcases that all shared the space with the other sundry items that lofts always attract. While in Queensland, Australia, the stuff goes under the houses raised on stumps: ‘gusunda’ - (David Malouf writes poetically about this zone in his novel Johnno); here in Shetland sundry items find their way up into the loft if the shed is full.

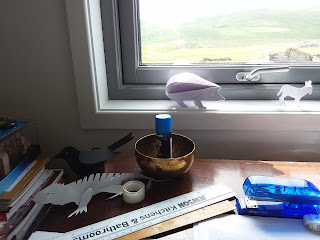

Only a few hours had previously been spent at the desk, pretending to be a ‘scholar,’ such was the self-conscious stance that generates nothing but indulgences that produce little of value other than a performance. The act was just testing the feel of and the view from the place, to see if they matched the original vision. Some writing had been done at this desk, but not much; a few cards had been cut out, but only a couple had been refined for completion. Other concepts had been experimented with, just to test the idea, the inspiration arising from the simple, everyday events that stimulate possibilities that need exploring. The surprising solution to make the long-legged, long-billed bird cards, the whaap - the Shetland name for the curlew - stand up had been discovered at this desk: then we had to pack up and leave. The cards were eventually made in Australia.

Now, on returning to Unst, it has been two weeks since one climbed up to the loft to switch the hot water on; nothing else. A quick look around showed that everything looked fine; there were other things to do than sit down at the desk. After settling back into the rhythms of cottage life and its routines, it was time to become familiar with the study once more. The ladder was pulled down and climbed. As the head moved into the void, one noted how dim it was; how it was slightly cooler than the space below - not bad for an area with no heating. The blind was raised to reveal the view and to let light into the room. The small, black LED lamp on the desk was switched on to illuminate the work place.

It was the paper water dragon on the desk that surprised. One had forgotten this experiment; the neighbouring black bird was as chirpy as ever - it was sister's birthday card. The little dragon looked good. The lamb and the hedgehog were not yet resolved, and stood as crude experiments needing more thoughtful variations: one always knows when one has the solution. The books were all in the order they had been left in. Familiar titles caught the eye with a gentle delight. The small, portable Buddhist shrine was unfolded as recognition of habitation and the richer, more complex things of life and love. One was home - that was when this piece was conceived. What was it about the experience that made this very modest space so friendly, so reverberant with emotion, with being ‘at home.’ What made this place feel so accommodating; so modestly ordinary but rich? And now, as I sit here before the western hills, the rain pummels the roof with a comforting sound, enhancing the experience of shelter . . . yes, of home.

One might say that home was like being with friends who ask nothing of one other than just being there, sharing stories and pasts, circumstances that are layered into each one’s experience; into each item here: how the desk was purchased; where; its story - (it originally came from Unst and was discovered as just the right size in a Lerwick antique shop; it had to fit through the manhole); and the Buddhist shrine, discovered in the charity shop along with a couple of Buddhist writings. Each of the other books on the shelves had similar stories, all purchased in Shetland, from anywhere, some online; some for almost nothing, and some for good money. There were some general interest publications, and a few valuable old historical tomes that came from the same antique shop as the desk. The aim has been to collect a small library of quality Shetland books; the search continues. The library also has the twin copies of those books one cannot live without, like Kenneth White’s Open World, and Alexander Carmichael’s Carmina Gadelica Hymns and Incantations. Then there are the surfaces of the room - every square millimetre was sanded and painted by myself; now the ceiling, walls, and floor, the doors and trims can be seen as other friends offering a greeting of quiet satisfaction.

It is still raining - the hills are now blurred by the weeping drizzle running down the windows. There is a gratification in just knowing, remembering; a happiness with being content in every way, comfortable; it is a simple space that loves life, being complex and ordinary, yet special in an extraordinary manner.

I look out and see the dykes - the dry stone walls; their zigzag patterning defining the fields. The chair itself joins the group of familiar friends - a little moulded plywood modern piece that reminds one of Christine Keeler with her suggestive pose. Its little movements add to the feeling of pleasure; the gentle wafting of the supported body that was first experienced with the classic Eames plywood chair in the university’s architectural library - at the University of Queensland - before it got gathered into the main library for better efficiencies.

All of this experience and recollection makes home - familiar; depth; feeling - no risk, no challenge: a knowing about knowing. ‘Home’ has nothing to do with grand designs or different displays. It has everything to do with modesty; the heart - those things modern architecture mock as irrelevant with its singular desire for slick, bespoke exhibitionism. One can recall how Mies van der Rohe ridiculed, even admonished Edith Farnsworth for her choice of furniture for his design.

Now, as I sit back, wafting, pondering, I realize that the glimpse of the loch sits centrally in the window. It are the little things like this that delight; that charm; that spin the spirit into an enchantment - that marvel of being home again; it is not unlike a cocoon, but it is not confining, just encompassing. It is something wonderfully satisfactory that is elusive of expression. So why try to explain it? One only makes the attempt because we need an antidote to architecture's great visions that seek the glorification of the individual, personal genius, and the admiration of everyone else. We need a lingering, rich, depth in architecture rather than the flimsiness of an heroic, skinny architecture – see: https://voussoirs.blogspot.com/2022/01/skinny-design.html

No one will look at this little re-build in amazement. It will stand merely as a part of the ancient landscape, unremarkable in its ordinary distinctiveness. It is not seeking recognition by way of the bespoke declaration; it just wants to be, and to accommodate being comfortably - at home; to let one be ‘at home.’ It is something architects need to rediscover - how to make our world our home. One only has to look at the architectural photographs in order to see the poverty of modernism that seeks enjoyment in voided, clean, contrived compositions rather than in the experience of ordinary, everyday living.

Consider the dry stone walls of the fields and know that there are years embodied in these structures; lives, hands, lands, place, thought, feeling – yet they toil not, neither do they spin: (Matthew 6:28 as quoted by Frank Lloyd Wright when writing of the architect of ancient times, called carpenter). The walls are relics left by others who knew this place, loved it; lived it; looked at the same horizon, the same hills, and pondered why, when, where . . - see: https://voussoirs.blogspot.com/2015/12/remembering-landscape-spirit-of-place.html This is home - being rooted in place known by others, knowing others, loving it for others to do likewise.

The rain falls on the land like a blessing - one hopes that this place can be shared with others yet to come. The gentle mists that are wafting in carry hope in their caring peace; a shrouding forgiveness. Architects need to know more of this sense of place, of being, and seek less of the grandiose startlingly difference in things creatively heroic. They need to learn how to speak gently, considerately, thoughtfully; how to shape homes as places; to make places as homes; how to astonish quietly and enrich, rather than amaze with an exaggerated, attention-seeking screaming. They need to learn how to encompass life and its living.

I go to switch off the keyboard and discover some scribbles left from last time - doodles and ideas to close off the hatch access for safety. The markings tell one of oneself - a forgotten self remembered, recalled: this is home; place and space that envelopes and enriches; something known; something as complex as the tiny shrine that one knows its good without knowing. We need to care for and entrust our feelings for life. Home is inclusive; holding one’s being there, engrossed, considered; sheltered in body, mind, and spirit.

A home is reeking with memories; with histories; with stories; it is a collision of memories enriching the present, striding into the future with a coherence of knowledge, understanding, and feeling stimulating contentment - wholeness. It is never a performance to attract the astonishment and envy of others.

16 MARCH 2022

John Berger And Our Faces, My Heart, Brief As Photos Writers and Readers, London, 1984.

p. 55/56

Originally home meant the center of the world – not in a geographical, but in an ontological sense. Marcia Eliade has demonstrated how home was the place from which the world could be founded. A home was established, as he says, “at the heart of the real.” In traditional societies, everything that made sense of the world was real: the surrounding chaos existed and was threatening, but it was threatening because it was unreal. Without a home at the center of the real, one was not only shelterless, but also lost in non-being, in unreality. Without a home, everything was fragmentation.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.