Union Street,

Aberdeen has always been an iconic urban attraction. It presents a

simple rigour in planning and expression that impresses as a civic

spine, a linear place. One is tempted to call the street an ‘axis,’

but it holds nothing axial about it. The street has its own inner

stability, something steady, strong and substantial. It has a satisfactorily 'rock solid,' Aberdeen ‘granite’ quality about it, which comes as no surprise. There is a contentment with the street's just being there, being itself rather

than working hard to otherwise display, link and connect, as axes do. So it was

that, on our return to Aberdeen while in transit back to Australia,

we were happy to once again spend a day strolling along Union Street

and exploring its precincts. The scant and scattered intrigues of

tourism had nothing to do with these essential delights that made

being there meaningful without special intent: see - http://springbrooklocale.blogspot.com/2012/06/who-or-what-is-tourist.html

Union Street, Aberdeen

Aberdeen

One particular

location along this ‘avenue’ has always been a memorable place. No, this is wrong: it is not an 'avenue' - ‘boulevard’ might be a better description; but this is still not right: 'boulevard' is too pompous for the dour Scots, too smart a term; too self-conscious. Simply, plainly and bluntly, ‘street’ is the best word for this

prominent, civic thoroughfare, a linear urban void that

authoritatively gathers the city in around its length, its strength. The

extraordinary place on this street is the Kirk of St Nicholas and its

environs. The churchyard has its own unique, stately presence in

the city as an island site. The church building, standing askew across the precinct, forms the core nodal mass of the complex that separates,

shapes and structures the various churchyard zones, while dominating the city’s skyline.

The kirk on Union Street

The Kirk of St. Nicholas

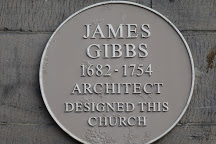

The plaque on the western front

The east end of the kirk

Approaching the Kirk of St. Nicholas from the east, passing Starbucks on the laneway leading from the shopping centre that

steals the church’s name, one is confronted with the grim, tall,

Gothic mass of the east end of the church with its bold, splayed

buttresses. These walls stand in an intimate relationship with public

space, defining it, dividing it, detouring it, organically

making and shaping the northern and southern entrances into the

churchyard in an invitingly casual, friendly manner. It is a

circumstance rarely seen in the architecture of today: the care for

the private and the public, the sharing of richness in twin

possibilities without compromise. One is reminded of Aldo van Eyck’s

‘twinness’ referred to in Team 10 Primer –

Alison Smithson, editor; MIT

Press, 1974.

The eastern gates to the churchyard

The path in from the north

Arriving at the kirk

from the north along Upperkirkgate, one walks beside a granite and cast iron

fence until its repetitive stepping is disrupted at the old Lodge to form a gated void that opens up into the pleasantly patterned paving of the graveyard.

Paths from this street entry adjacent to its shopping centre neighbour, lead to the northern church doorway, connect with the eastern entry, and continue to the main western front. The

spaces around the kirk are quietly welcoming, and have seats

that invite one to pause and ponder. “There, but for the grace of

God . . .” said one passerby as I photographed the gravestones: indeed. The grey, weathered, shadowy mass of the kirk provides a

solemn background for the ancient gravestones that tell of other

times, other lives. These darkly grim church walls slice across the site in the prescribed east-west orientation, ignoring all other alignments as they define their own

twinned identities of interior and exterior place. Again one recalls van

Eyck’s writings in the Primer - ‘place, not space.’

The west door

The western gates opening to Back Wynd

At the classic western

front, one is confronted with a typical church door – twin, large

and massive – standing above a formal set of four stairs opening

out as a platform projecting into a tiny courtyard zone, the western

entrance. This approach also happens to be the vehicular access for the site.

The gateway opens onto the narrow lane, Back Wynd,

connecting Union Street on the south with Upperkirkgate on the north.

Shops along this wynd make it an interesting inner-city alleyway. This side boundary of the churchyard that encloses the

graveyard is one of the most memorable walls in the world – see:

http://voussoirs.blogspot.com/2016/09/aberdeens-wall-place-between.html

Here gravestones stand against the boundary and, from the lane, form an ad hoc, profiled top that is surprisingly, astonishingly beautiful. This dividing element gives a twin significance to both its sides,

providing a modest background for the dominant grave stones on one side,

while highlighting the shaping of their prominence as ‘shadows’

on the other, all without exaggeration of embarrassment. It is a mesmerising civic sight: a simple, unapologetic

joy that considers, acknowledges and encompasses the necessities of life and death

at the interface.

Back Wynd wall

Union Street

As if this casual

interweaving and integration of spiritual place into the everyday city circumstance

on the east, north and west was not enough, the approach to the kirk

from the south, off Union Street, offers one of the grandest, genuine

gestures to the street that one can see. In all of the chat about

context and place in modern architecture, their singular

significance and pertinency, there is nothing as deliberately beautiful, as subtle and engagingly self-consciously prominent as the Union Street entry

screen/gateway. It stands like a bold, urban folly, but one rich with meaning, identity and relevance.

The path leading in form Union Street

This element sits

comfortably with the presence and pattern of the street, its consistence, matching the substance of and detail in

the elevations of the neighbouring buildings that make the street, just as the street makes them.

Instead of a contrasting, green, open gap, like a missing tooth in

the continuity of the street frontage, the churchyard has been given a deliberately formal facade

that replicates the colour, scale and massing of the adjacent

architecture without mimicry, creating a screen/gateway that defines both public place and graveyard privacy, boldly mediating

between life and death. This structure is a large array of columns topped with a simple stone entablature, and with metal screen/fencing elements in

between. That such an effort could be made both to identify the kirk and its yard, and to acknowledge the street, to recognise and harmonise ‘twinness’

with its structural scale, sense, detail, and experience, is

remarkable. It is this element alone that makes Union Street so

significant, as the gateway-screen reinforces everything that the street is

about: the classic forms confirm a meticulous, calculated

purpose; the street’s civic deliberateness. This is Aberdeen at its best.

The screening-street element shapes the main gateway entrance to the kirk that

opens onto shady, leafy paths. These 'crazy-paved' paths branch off to the various other

entrances to the precinct, north, west and east, and to the kirk's doorways. Seats

encourage one to share the quiet of the place, its reverence. This is

hallowed land, a place for the dead, for the past to be remembered,

for contemplation, for worship; but it is a welcoming place for the living too, not a

mere sombre, no-man’s-land retreat into the fearful void of bleak

nothingness, suggesting a gloomy hopelessness. Here, the place for the dead has been

intertwined with daily city life, twinned purposefully with it as yin and

yang. The kirk's precincts are not only a destination for quiet recreation, their paths also offer refreshing thoroughfares, interesting detours to other parts of the city beyond: the stones integrate and intermingle with the surrounding lanes and streets.

The south door

The graveyard has become a green retreat, a gentle refuge from the

business of the street, as well as a place for the dead. Folk stroll and pause,

not only to reflect on other people and other times – the history

is astonishing – but they also pop in for lunch; for a rest, a

break; to enjoy the sun, a chat; sometimes just to take a different path to elsewhere, maybe a shortcut. There is nothing overwhelmingly

bleak about the gravestones: they are friends that remind one of the

reality of life, its transitoriness; its brevity: they tell stories or are just there, depending on what one is seeking, feeling.

Sometimes these weathered and worn stones, in their table form,

provide a spot for one to squat on while snacking during a break from

the office, or while just gathering one's thoughts. Strangely, this ad hoc usage shows more respect than any

rude disregard, an intimate sharing and caring, with the grave marker happily being offered as a seat. The kirkyard is truly

a remarkable place because of what it is and how it is used. That

these functions have all been encouraged and shaped by the plan, the strict orientation and placement of the kirk building, and the detailing of its kirkyard

boundaries, shows a sensitivity to a self-conscious civic involvement

that seems to evade the understanding of modern architecture.

Table graves

There is something

modest here that humbles one, something, on reflection, more than the

graves might usually offer to the living. The only concern was that the kirk

itself was locked, opened to the public on defined occasions

that did not include one of the times we were there. This disturbed

the concept of the open and friendly precinct that eventually stifled

the welcome with exclusion, creating a central black hole, establishing the kirk as a boundary.

An image had been seen a couple of years ago in an Aberdeen arts publication that suggested that this was a ‘sideways’ kirk: see - http://voussoirs.blogspot.com/2017/04/shetlands-sideways-churches-creativity.html One was keen to see the interior in order to check, to confirm this possibility. Alas, this was not to be. Even though there were signs of habitation – vehicles nearby, and lights on – all knocks were ignored and locks were left unopened. The '11:00am Sunday service' notice seemed to mean nothing. Did the church not want worshippers? We were there on a Sunday at the right time, but there was not one open door, nor any service, just the usual friendly, open access to the graveyard. The need to know the layout became a minor obsession. This could be important in understanding the ‘sideways’ development, opening up a new scale of operation in this form of planning. The exterior was explicit, but what was the interior? It was not clear.

An image had been seen a couple of years ago in an Aberdeen arts publication that suggested that this was a ‘sideways’ kirk: see - http://voussoirs.blogspot.com/2017/04/shetlands-sideways-churches-creativity.html One was keen to see the interior in order to check, to confirm this possibility. Alas, this was not to be. Even though there were signs of habitation – vehicles nearby, and lights on – all knocks were ignored and locks were left unopened. The '11:00am Sunday service' notice seemed to mean nothing. Did the church not want worshippers? We were there on a Sunday at the right time, but there was not one open door, nor any service, just the usual friendly, open access to the graveyard. The need to know the layout became a minor obsession. This could be important in understanding the ‘sideways’ development, opening up a new scale of operation in this form of planning. The exterior was explicit, but what was the interior? It was not clear.

The uncertainty of the interior that appears axial

Back home, the

search for more interior photographs and the floor plan began. The

photographs were never quite distinctive enough to be sure, certain,

but eventually the plan was discovered and printed. This was not one

church, but two: twins – a West Church, (‘Seats for 1100’), and

an East Church, quaintly named ‘Quire,’ (‘Seats for 1700’),

as if it might be the choir of an integrated Gothic church space. At the

eastern end of the East Church was St. Mary’s Chapel and the

vestry, the spaces that were enclosed by the massive walls that

framed the eastern laneway approach. The chapel had its own strange

history. Apparently witches had been locked up here in the sixteenth

century witch-hunts prior to their trails and death. Between these western

and eastern places of worship, were the massive arches below the

central tower that formed part of the enclosure of what was labelled

in bold, Gothic lettering, ‘Drum’s Aisle’ and ‘Collison’s

Aisle.’

This obscure 'Gothicked' labelling had originally been misread as ‘Drum’s Hisle,’ and

was Googled as this to see just what it was referring to: an

individual’s Christian name? It made little sense. Soon it became

clear that the word was ‘Aisle.’ One of the references that was

followed up turned out to be in Google Books, that cleverly

highlighted the words ‘Drum’s Aisle’ in the text of an old

publication on the history of Aberdeen by Robert Wilson, A.M., An Historical Account and Delineation of Aberdeen, published in 1822.

Google Books

It was in this text

that the Kirk of St. Nicholas, its history, form and interior, were described in intimate and specific detail

(Sacred Edifices p.68 – 79) – see:

https://books.google.com.au/books?id=HWY_AQAAMAAJ&pg=PA70&lpg=PA70&dq=drum%27s+aisle&source=bl&ots=PPiIeBMu8Z&sig=fwhbmFXrTv8STzoOeQN_5Bsk8qc&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwilgvvWvYTdAhWVHXAKHRAQCdoQ6AEwEXoECAgQAQ#v=onepage&q=drum's%20aisle&f=false Wilson comments that the pulpit of the Western Church is ‘located on the central pier.’ This could now be confirmed in the re-reading of some of the photographs. So this plan has the

elements of a sideways kirk, but comes with an upper gallery or

mezzanine on all four sides of the kirk. If one removed the southern

spaces and gallery behind the pulpit, one would have the typical

‘sideways’ plan. (Streetview - see below - seems to suggest that these spaces are service/circulation areas.)^ Could this variation be an early version, an experimental

scheme, trying out a different layout, perhaps in response to a new

understanding of the liturgy, or the desire to break from the old?

While of interest, the West Church plan seemed awkward and messy,

unlike the tight functionality of the Shetland ‘sideways’ plan.

Could it have been inspired by the East Church layout?

There was a puzzle with the East Church: this plan looked smaller in area, but the note said that it was able to seat 600 more people than the West Church. This enigma was solved by

the old text that described the East Church as having ‘galleries on the

north and south, and double-height galleries on the west.’ This setout shaped the space precisely in plan as the model

for the ‘sideways’ kirks; but this was no ‘sideways’ plan: it

was a squat, short, east-west axial basilica plan with galleries. Did

the newer West Church attempt to recreate the East Church layout in a

rectangular profile? Is this the early days of the development of the

little Shetland ‘sideways’ kirks that do likewise, but more successfully?

All church spaces in the Kirk of St. Nicholas had corner stairs typical of the ‘sideways’ plans and suggested

the beginnings for this unique inversion in Shetland worship. The

Robert Wilson book did not comment on any plan beyond factual description, but it did explain the unusual naming of the core

spaces: these ‘Aisles’ referred to the names of the Drum family

and the Collison family, and were burial places for these lineages,

now used otherwise for entry and kirk meetings.

Drum's Aisle

The screen to the kirkyard in context

Union Bridge

Browsing through the

old text and its 'delineations' was interesting as it had numerous engravings of buildings and

bridges of old Aberdeen. One could recognise it immediately – Union

Bridge. Even though illustrated in its original context prior to the

construction of Union Street and its associated development, the

current street experience of this bridge, its environs and details, remain clear and recognisable in this engraving. The sense of this

strong link to other times impressed; it gave substance to our more

flighty, self-indulgent era.

This published collected and illustrated history of Aberdeen is a

remarkable text that describes noteworthy places very precisely,

thoroughly, and carefully. One can still enjoy Union Street today,

and the Kirk of St. Nicholas: their essence, substance, remains in tact, with very little modification. They still dominate the modern world, and remain special places in spite of the change, ordinary but extraordinary in

nearly every way. They are places for people, twins within twins, twinning, welcoming and supporting the life of the everyday; embodying simple city life

without pretence or posing; without slick style, sly pomp, or sleek

circumstance. They have much to teach us by way of obvious example:

but will we learn as we continue to eulogise bespoke differences and

extremes, and turn our attention away from the wonder of things

ordinary and the joy of their use, their unselfconscious, unpretentious experience? It is the

ordinary that we ignore at our peril, as if we might know better.#

The kirk and yard prior to the construction of Union Street

#

Here, again on the

graveyard theme, one thinks of the new graveyard expansions on Unst,

Shetland – in particular, the Baliasta Kirkyard comes to mind.

While being beautifully detailed and nicely, sensitively set out and

finished, the graves in the new yard are positioned north/south, as

if the strict east/west of the old layouts meant nothing. There might

have been some efficiency involved in planning or some other

reasonable excuse, but the old symbolism did mean something –

facing the ‘Son of Man’ rising in the east on resurrection* - and

needed respect and recognition rather than rejection in favour of

modern calculations and visions. In the Lund Kirkyard, the new graves

are located east/west, but strangely turn their backs on the path

that leads through to the old yard, as if they intend to ignore the

living. Just why the stones face west when all others in the old yard

face east, remains a planner’s puzzle yet to be solved. Such is

modernity.

* NOTE:

The

traditional Christian method of positioning the coffin or shroud

covered body in the grave was to have the body with the head to the

west, feet to the east. The body was placed face up. When it was not

practical to use the west-east position for the grave, a north-south

positioning was the next best option. There the body would then be

laid on its side, head to the north and facing east. Not all burials

followed the tradition nor did all cemeteries.

The reason for the

east facing position is offered by Tom Kunesh:

Note that in

Christianity, the star (of the Jewish astronomers from Iraq

[Babylon]) comes from the east. Then there is Matthew 24:27 (NKJ):

“For as the lightning comes from the east and flashes to the west,

so also will the coming of the Son of Man be ...” thus for the

Christian believer in the resurrection of the dead, placing the body

facing east will allow the dead to see the Second Coming of Jesus.

P.S.

The Google Books

text spoke about the upper gallery of the East Church as being 'for

seamen,' as it had a model ship suspended over it. This seems to have

more to do with the symbolism of the ship rather than any specific

occupation: see -

http://voussoirs.blogspot.com/2017/02/ulvik-church-norway-tradition-in-timber.html

SOME COLLECTED IMAGES

UNION STREET & TIME

Aberdeen 'Granite City'

^

STREET VIEW

One has to remember

Street View: see –

http://voussoirs.blogspot.com/2017/10/the-need-for-street-view-in-architecture.html

Visiting the Kirk of St. Nicholas, Aberdeen in Google Earth, clicking

on the little figure, and browsing the Street View options along the

blue lines or at the various blue dots is really informative. It

reveals the importance of Street View in architecture yet again. Here

one discovers not only the environs of all locations around the site

and in the graveyard, but also 3D images of the interior of the West

Church, the Drum’s Aisle, the bells in the tower, and the clocks

above. It is a wonderful tool that highlights the ‘sideways’

structure of the space, and suggests that the East Church is being

renovated or restored. There are no interior images of the East

Church, but one glimpse through the door of the Drum’s Aisle seems

to show the space as a building site. One has to rely on Robert

Wilson’s description to understand this space.

NOTE

6 JAN 2019

A copy of the Reader's Digest publication, The Best of Britain and Ireland from the Air, published in 2011, was recently found in a secondhand bookshop and purchased. It had photographs of the Shetland Islands and the Orkneys. Just why Papa Stour was selected to be 'the best' of Shetland remains an enigma. Maybe the photograph was just readily available for this 'digest'?

On perusing the publication later, an aerial image of Aberdeen was discovered. It was interesting to see Union Street and the kirkyard of St Nicholas in the context of the city. The street holds the same authority from the air as it does at street level. The harbour with the ferry that services the Shetland Islands can be seen on the bottom right of the photograph, close to the western end of Union Street.

NOTE

6 JAN 2019

A copy of the Reader's Digest publication, The Best of Britain and Ireland from the Air, published in 2011, was recently found in a secondhand bookshop and purchased. It had photographs of the Shetland Islands and the Orkneys. Just why Papa Stour was selected to be 'the best' of Shetland remains an enigma. Maybe the photograph was just readily available for this 'digest'?

On perusing the publication later, an aerial image of Aberdeen was discovered. It was interesting to see Union Street and the kirkyard of St Nicholas in the context of the city. The street holds the same authority from the air as it does at street level. The harbour with the ferry that services the Shetland Islands can be seen on the bottom right of the photograph, close to the western end of Union Street.

The ferry is in the upper portion of the harbour that is so snug that the boat has to turn and reverse into its berth.

The significance of the kirkyard is also clearly revealed from above. It is a core inner-city green space. The aerial view makes its importance clear: it is a place that connects as well as one that offers refuge from the busy streets for relaxation and contemplation.

The unique east/west alignment of the kirk is evident from this viewpoint too, highlighting the presence of this dominant civic landmark in the image of the plan as well as that of the cityscape.

The various N, S, E & W approaches to the kirkyard are clear from the air, as are the pathways around the kirk.

The deliberateness of the formal Union Street screen can be appreciated from above.

The Shetland Islands ferry berthed in Aberdeen harbour

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.